How Sustainable Investing Can Create Long-Term Value

Sustainable investing (SI) is an investment approach that considers environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, alongside financial ones, in the pursuit of competitive returns and positive impact for people and planet. Companies and individuals alike recognize that corporate behavior impacts society and the environment. Some of these impacts are plainly visible, while others rear their heads as quantifiable positives or negatives on the broader economy and corporate balance sheets.

As such, sustainable investors assess the ESG factors that they deem material to prospective investments alongside traditional financial analysis to inform their investment decisions. Sustainably managed assets have grown consistently in recent years, riding a tailwind powered by changing consumer demands and an influx of new investment products. Increased recognition of SI as a bona fide investment approach helps too, as investors realize that doing good with your capital doesn’t have to be synonymous with sacrificing returns. Rather, it can be additive to capturing long-term value in their portfolios.

Looking Beyond the Balance Sheet

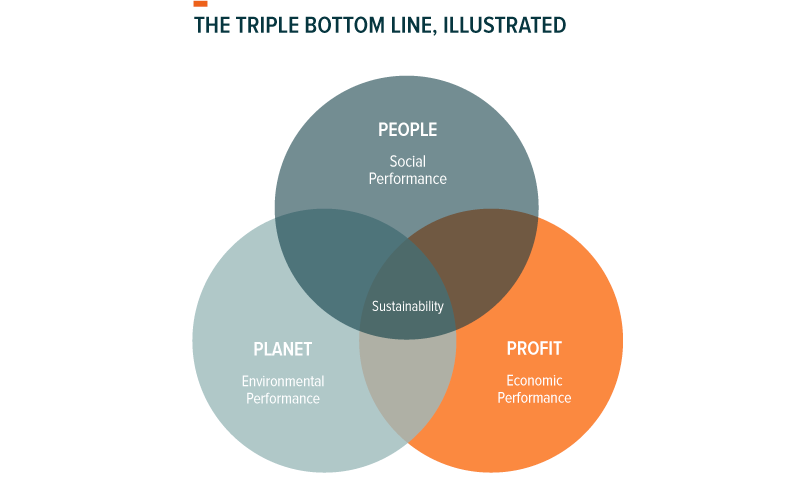

The triple bottom line (3BL) is an accounting framework that considers environmental and societal impacts alongside the traditional profitability metrics.

The 3BL serves as a lens for assessing how sustainable a company is and reveals that sustainability considerations and financial value are inextricable. Below, we explore the 3BL’s environmental and social components and how they can relate to financial performance.

Environment: The relationship between corporate behavior and its effect on the environment predates the Industrial Revolution. But until recently, investors largely ignored the relationship. Today, the investment community increasingly recognizes the irrefutable, causal dynamic between the two.

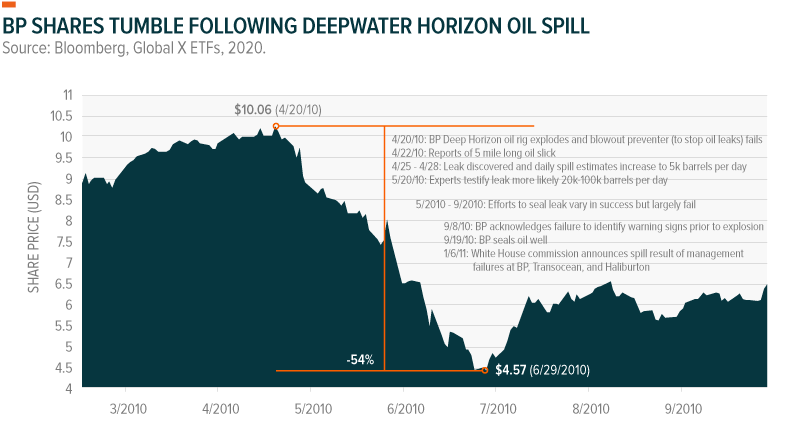

One example where corporate behavior had direct effects on the environment is the Deepwater Horizon oil spill that started when a BP-operated oil rig exploded. More than 4.9 million barrels of oil emptied into the Gulf of Mexico over 87 days, damaging over 1,300 miles of coastal habitats and irreversibly altering deep-sea ecosystems.1,2 Economies suffered: according to one estimate, Gulf fisheries lost out on $8.7B in revenues from 2010–2020. The Gulf’s tourism industry reportedly lost $22.7B from 2010–2013.3

A government commission found that “time- and money-saving decisions” contributed to the accident.4 Some of these decisions include, but are not limited to:5

- Not running cement evaluation logs – cement is key in controlling pressure levels, a key contributor to the explosion

- Improperly interpreting negative pressure tests – these tests help indicate cement-job integrity

- Not installing additional physical barriers, outside of cement

BP paid over $70B in fines and settlements in the 10 years after the spill. The company’s shares have yet to fully recover.6 As of February 10, 2020, they remained 29% lower than their pre-spill value.7

Society: Companies are essential threads in society’s fabric. They provide jobs, income, and training while producing the goods and services that people consume. Increasingly, society demands that companies respect the communities in which they operate. Not fulfilling this obligation can have devastating consequences, whether intentional or not.

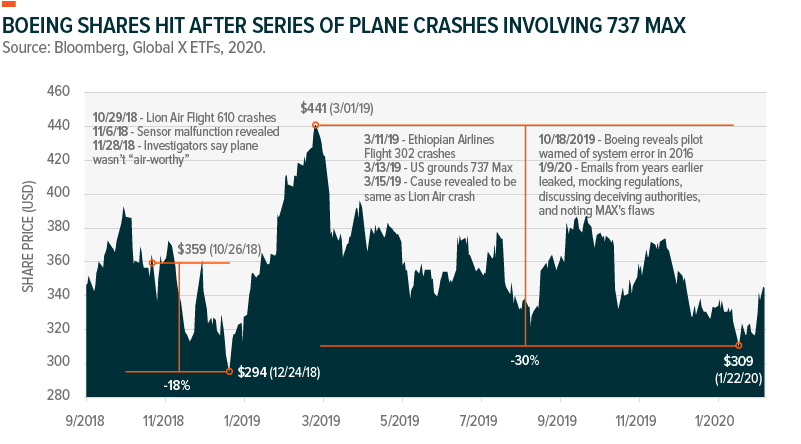

For example, inadequate safety procedures and general negligence at aerospace manufacturer Boeing contributed to multiple fatal crashes involving its 737 MAX airplane. One such error, among several others, included not teaching pilots how to override the automated plane stability system (MCAS) that malfunctioned and led to the crashes. A Boeing engineer eventually revealed that, to cut costs, the company forwent the installation of a safety system that could have mitigated the malfunction, a clear violation of stakeholder interests in the name of short-term profitability.8

Boeing’s short-term thinking could harm its long-term profitability. Families lost loved ones, communities lost valued contributors, and because of its negligence, Boeing lost a meaningful share of its reputation. The stock tumbled almost 22% from previous highs following the second crash.9 In 2020, Boeing reported no January jetliner orders for the first time in over 50 years.10 And the effects of a tarnished reputation don’t just hurt shareholders. Because Boeing is a major employer, both directly and through its suppliers, the societal impact of Boeing’s oversight could result in significant lost wages or lost jobs for thousands of workers who depend on the company for their livelihoods.

Optimizing 3BLs with Good Governance: How can companies – and investors – ensure that the right mechanisms are in place to minimize exposure to environmental and social risk? It starts with good governance.

The examples above highlight extreme negative outcomes that resulted from short-termism, a mindset where achieving short-term profits takes precedence over other considerations. Often, short-termism manifests as cost-cutting designed to boost earnings rather than build long-term value. Good governance rejects this idea. Instead, it focuses on being a good steward of shareholder capital by making decisions oriented toward the long term, also known as long-termism. The Harvard Business Review lists a number of features a company with healthy governance exhibits:11

- A strategic, and not overly financial, approach to resource allocation

- Concern for corporate citizenship and ethical issues beyond what legal and compliance requires

- Attention to environmental and political risks

- Links between executive compensation and strategic goals

- Staggered board terms to facilitate continuity and transfer of knowledge

Companies that adopt these behaviors may outperform those with short-term oriented governance structures. In their academic study, “The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance,” Harvard researchers identified 90 high sustainability companies that had long-term oriented policies and 90 low sustainability companies without such policies. Tracking $1 invested in value-weighted portfolios across the two groups from 1993 to 2010 revealed that the high sustainability portfolio outperformed by almost 47%.12 And even more telling, the analysis period predates today’s keen focus on sustainability-oriented corporate governance.

So, sustainability doesn’t just refer to a zealousness for the environment or social good, though both are certainly welcome. Seemingly, sustainable companies are those built for the long haul.

Investing for Good—and Long-Term Value

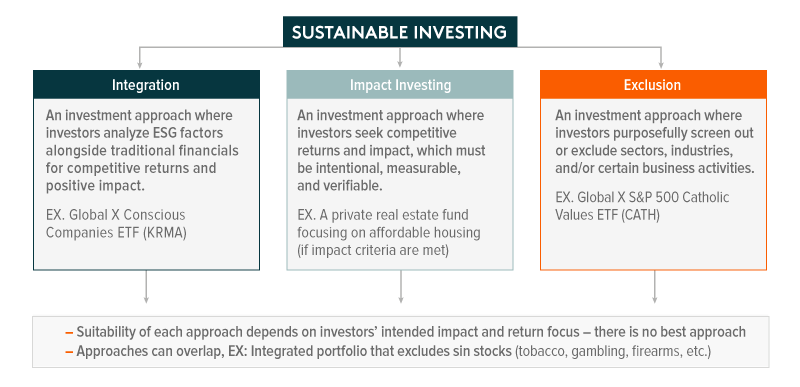

Prudent investing entails careful consideration of the factors that paint companies’ risk/reward profiles, and it’s becoming increasingly clear that E,S and G factors can be financially material. Their inclusion in investment processes paints holistic investment rationales geared to capture long-term value and generate positive impact. This approach falls under the sustainable investing umbrella and is aptly termed ESG integration. Different than exclusion, where investors blacklist certain sectors or business activities, those who practice integration analyze ESG factors to find high quality companies across sectors and industries.

How can investors integrate ESG factors process-wise? First, investors contextualize quantitative and qualitative ESG data to establish a set of factors. Then they weight the factors depending on how relevant they are to companies’ respective sectors and industries – this relevance is also known as materiality. Some investors develop their own data methodologies and materiality schemes. Others rely on external providers for all or parts of their processes. As long as asset managers demonstrate a process-driven consideration of ESG factors without compromising their investment processes, there is no wrong or right approach to integration.

The Global X Conscious Companies ETF (KRMA) is an example of a fund that utilizes ESG integration in its investment approach. KRMA tracks an index that considers the impact companies have on stakeholders that are critical to the companies’ success: customers, employers, suppliers, stockholders and the community at large, alongside traditional financial metrics. The index relies on a wide breadth of qualitative and quantitative information to gauge positive stakeholder outcomes, the materiality of which varies by stakeholder group. A composite analysis then generates a single score for each company by weighting outcome metrics and factoring in more traditional financial research. Lastly, top names go through a screen to identify which companies met inclusion standards in the three years prior.

Performance is one thing, but sustainable investors also want their investments to do good . Though it can be difficult to gauge the impact of an invested dollar, integration can signal which practices investors deem as acceptable. As capital increasingly flows to responsible companies, other investors could view the resulting momentum as a positive sign and invest themselves. Ideally, companies recognize the source of positive investor sentiment and maintain their standards, while less responsible companies are motivated to improve theirs.

Investors looking to drive direct change can participate in active ownership, exercising their rights as shareholders to engage companies. This is best done by filing shareholder resolutions and proxy voting. Shareholders can work with other shareholders who share similar values and bring up issues at a company’s annual meeting and vote on them. The approach can be effective: in 2016, a Kellogg shareholder resolution urging the company to switch to cage-free eggs made it on the proxy statement and received 95.9% of votes.13

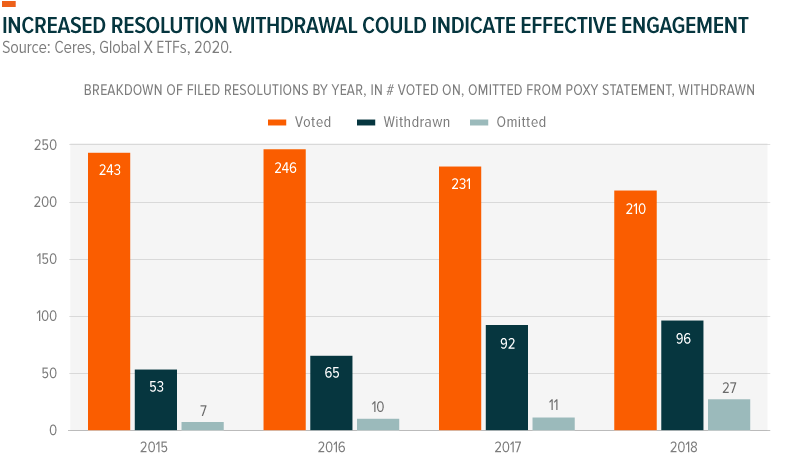

Critics of this approach like to point out that few sustainability-oriented resolutions pass a vote. However, the power of engagement also lies in open dialogues, as shareholder resolutions can still attract media coverage and inform the public. Frequently, companies and shareholders negotiate prior to annual meetings. Companies often make concessions in exchange for shareholders withdrawing their resolutions. Of 108 environment-related resolutions filed in 2018, shareholders withdrew 47 of them, citing firm commitments, open dialogue and strategic withdrawal.14

Sustainable Investing: Not Just a Passing Fad

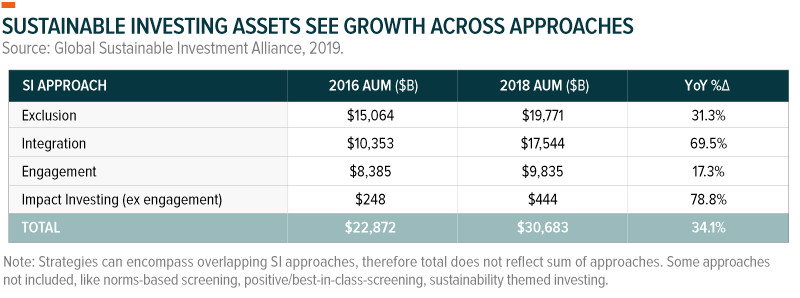

Investing through a sustainable lens is not just the trendy investment approach du jour. The fact that sustainable assets represented 1 in every 4 professionally managed dollars in the US in 2017 says as much.15 Between 2016 and 2018, global sustainable investing assets under management (AUM) grew 34% from $22.8T to $30.7T.16 Of the three primary sustainable investing strategies, which can overlap, integration increased 69% over those two years to $17.5T. Exclusion increased 31% to $19.7B and engagement 17% to $9.8B.17

Institutional assets, meaning those managed for pension funds, universities, foundations and insurers, represented 75% of sustainable AUM in 2018. Notably, retail assets made up the remaining 25%, a 5% increase from 2016.18 While institutional investors’ affinity for sustainable investing is well known, especially outside the US, retail-directed sustainable investments are just starting to gain traction.

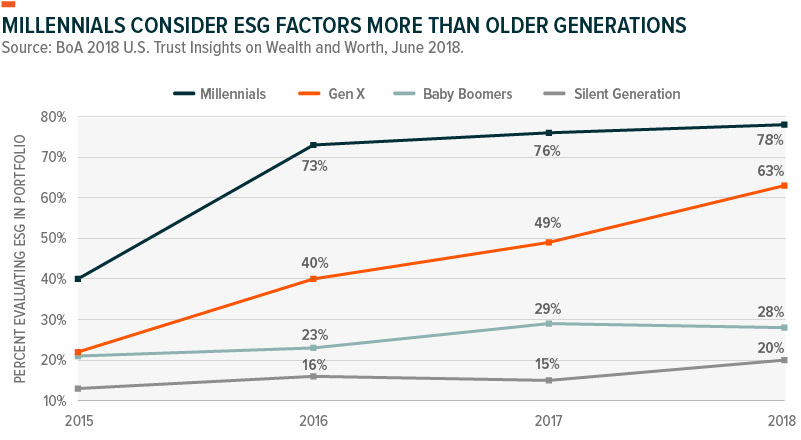

Some of this momentum comes from investor demand, rooted in the investment community’s changing demographics and respective values. Millennials, for example, value corporate sustainability more than previous generations.

A Nielsen survey found that 85% of Millennials felt that it is important for companies to implement environmental programs, versus just 72% of Baby Boomers and 65% of the Silent Generation.19 Further, 78% of Millennials evaluated their portfolios for sustainability considerations in 2018, compared to just 20% of Baby Boomers.20 We expect Millennial-driven momentum to accelerate as Millennials enter their peak earning years and grow their investible assets.

Asset managers are evolving too, creating new investment strategies to serve these changing demographics and SI’s recognition as a competitive investment approach. According to Morningstar, 133 sustainable funds launched from 2015 to 2018, of which 56 were ETFs and 77 were open end mutual funds. For comparison, just 87 sustainable funds launched in the 10 years prior.21

What Should I Take Away from This?

Tangible examples make it clear that corporate behavior impacts the world around us – socially, environmentally, and economically. Sustainable investing techniques incorporate these considerations to create robust, long-term assessments of companies’ value. Despite sustainable investing’s growing popularity, in our view, the peak is not yet in sight. As data improves and awareness broadens, we expect sustainable assets to grow in the years to come.

Related ETFs

KRMA: The Global X Conscious Companies ETF is designed to provide investors an opportunity to invest in well-managed companies that achieve financial performance in a sustainable and responsible manner and exhibit positive Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) characteristics.

CATH: The Global X S&P 500 Catholic Values ETF provides exposure to the companies within the S&P 500 whose business practices adhere to the Socially Responsible Investment Guidelines as outlined by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) and excludes those that do not.